Egress Fees Explained: How Data Transfer Pricing Really Works

This guide breaks down data transfer pricing and how to lower your egress costs. We lay out practical ways to estimate monthly data transfer cost, map where data goes, total the bytes on each route, and apply the rates that match those routes. We then focus on changes that usually lower your egress fees, such as improving caching, shrinking payloads, and avoiding chargeable boundaries.

#What are data transfer costs?

Data transfer costs includes all charges of moving data (ingress, egress, and sometimes inter-region traffic) into, out of, or between servers and networks. Typically you pay data transfer costs whenever your infrastructure sends or receives data across network boundaries.

Egress fees are typically the most expensive part of data transfer costs. Most cloud providers offer free or very cheap ingress (incoming data), but charge significantly for egress (outbound data to the internet) because it consumes expensive network bandwidth and infrastructure capacity.

#How does data transfer pricing work?

Data transfer pricing is the cost of sending data out of a provider’s network. Most of the time, that means traffic delivered to users on the public internet. It can also include data that crosses zones, regions, or providers.

Providers tend to follow two pricing patterns. Some meter transfer and bill per GB or GiB, often with tiers and destination-based rates. Others bundle a monthly outbound allowance into a plan, then charge an overage rate once that allowance runs out.

Transfer charges are not limited to internet delivery. They can also appear within a single provider when data crosses zones or regions. A single payload can be counted more than once if it crosses multiple chargeable boundaries before it reaches its destination. Services in the path, such as NAT gateways and some load balancers, can also add separate usage fees.

#What are egress fees?

Egress fees are charges cloud providers apply when data leaves their network, typically when you transfer data from your server to the public internet or another region.

In simple terms, you pay egress fees when your infrastructure sends data out, such as serving website traffic, delivering files, streaming content, or syncing data across cloud providers.

That’s why high-traffic applications that send large amounts of data out to users or other system (streaming, SaaS platforms, APIs, blockchain nodes, AI workloads) often see egress as one of their largest cloud cost drivers.

#Data transfer cost meaning in practice

Data transfer cost is a charge based on the amount of data transferred, not bandwidth or a measure of performance. Providers usually bill egress fees monthly.

A simple way to picture it is a page load or an API call. A request arrives. The response is sent back to the user. Inbound transfer is often not billed separately, while outbound data is commonly billed as data transfer out.

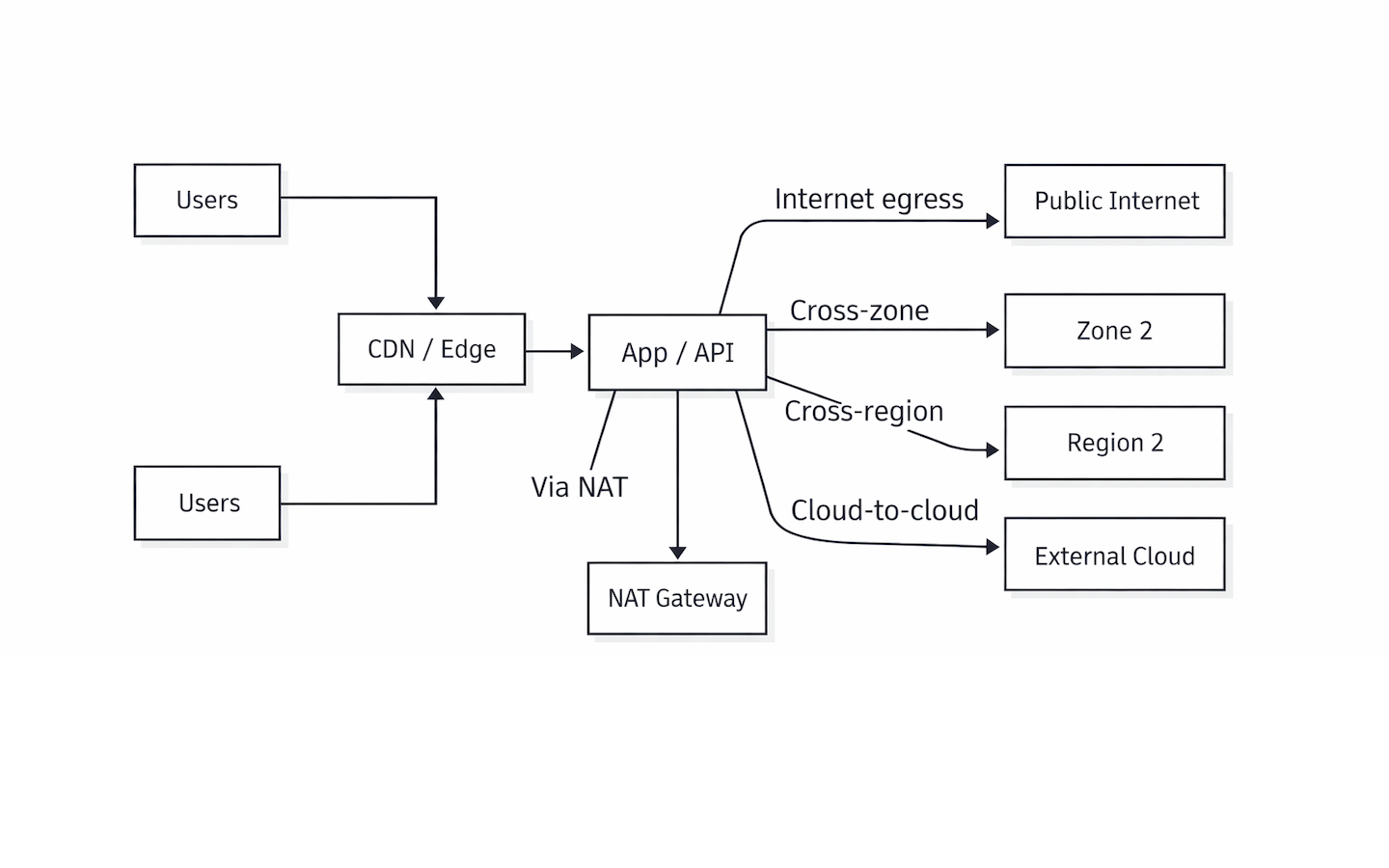

Most data transfer costs come from a few common paths:

- Internet egress: Data sent to users on the public internet, such as responses and downloads.

- Zone and region transfers: Traffic that crosses zones and regions, plus data copied to another region for replication or backups.

- Cloud-to-cloud transfer: Data sent from one provider to another over the public internet.

- Private subnet egress: Outbound traffic routed through a NAT gateway, which can add separate hourly and per-GB processing charges.

This is why the traffic route matters more than the headline per-GB rate. The same payload can be billed multiple times when it crosses multiple chargeable boundaries en route to its destination.

Optimize your cloud costs with Cherry Servers’ private cloud—a flexible alternative to on-premises infrastructure.

#How providers charge for data transfer

Providers do not use one single pricing method. Most bills are built from a few common charging rules, based on where the traffic goes.

#Metered internet egress

This is the classic model. Data sent to the public internet is billed per GB or GiB. Rates often vary by region and destination.

Azure includes the first 100 GB per month of internet egress for free, then charges outbound transfer at published rates.

#Intra-cloud boundaries

Traffic can be billed even when it stays within one provider. Zone and region boundaries are common triggers.

On Google Cloud, traffic to or from an external IPv4 address is treated as leaving the zone. Inter-zone data transfer charges can apply in designs that appear to sit in one zone.

#Network services that add processing charges

Some services sit in the traffic path and add their own usage charges. These fees can stack on top of basic data transfer.

Common examples:

-

AWS NAT Gateway

AWS charges an hourly rate for the gateway, then adds a separate fee based on the number of gigabytes it processes. This cost shows up most often when private subnets reach the public internet.

-

Azure NAT Gateway

Azure bills for the gateway resource time and for the data it processes. Depending on the traffic path, bandwidth-related transfer charges can still apply alongside the NAT fees.

-

Cloud NAT(Google Cloud)

Cloud NAT uses a base hourly charge and a usage charge tied to the amount of data processed. This becomes noticeable in designs that push a lot of outbound traffic through private networks.

-

Application load balancers

Many load balancers use a usage-based model instead of a flat monthly price. Charges often scale with capacity signals such as new connections, active connections, and bytes processed.

#Bundled transfer allowances with overage

Some providers include a monthly outbound transfer allowance in the plan. Overage is billed only after usage exceeds the included amount.

DigitalOcean includes an outbound transfer allowance with products like Droplets and Spaces, then charges overage once usage exceeds the included amount.

#95th percentile and port-based billing

In colocation and some dedicated server setups, billing is often based on bandwidth rate over time, not total GB.

The 95th percentile model drops the top 5% of usage samples and bills based on the highest remaining rate.

#CDN delivery versus origin transfer

CDNs change where data transfer is billed. Delivery to users is billed at the CDN edge, and origin-to-CDN transfer can be treated differently.

When traffic is served through CloudFront, data transfer between CloudFront and AWS origins is waived.

#How to estimate your monthly data transfer cost

A good estimate is simple. List where data goes, total the bytes for each route, then apply the matching pricing rules.

#Pick an estimate window

Choose one month as the estimate window. Use that same window for every number you collect or model.

#List the routes that can generate charges

Start by listing where your application sends data. Include anything that goes to end users, another zone, another region, cloud, or out through NAT.

Every connection represents a route that needs a monthly byte estimate.

#Tag each route

Add a short tag to every route. These tags become the buckets you price later.

-

Internet egress

This covers data delivered to end users or any destination on the public internet.

-

Cross-zone

Cross-zone transfer covers traffic exchanged between availability zones in the same region. It includes service calls, database reads, and cache traffic that leaves one zone for another.

-

Cross-region

This includes data transferred between regions. It most often comes from replication, backups, and multi-region failover designs.

-

Cloud-to-cloud

Cloud-to-cloud transfer covers data sent from one provider to another.

-

In-path processing

This includes usage charges from services in the route, such as NAT gateways and load balancers.

Some routes need more than one tag. NAT egress is a common example. It is outbound traffic, and it can also carry a processing charge.

#Estimate monthly bytes

If the workload already exists, use the provider’s detailed billing report to pull monthly totals for transfer and network services. If the workload is new, model the bytes from traffic and payload size.

#API and page responses

Start with the request volume. Then check the response size. A tiny request can trigger a large JSON payload, HTML page, or file download. Monthly outbound equals requests per month multiplied by average response size.

#Static assets and CDN traffic

Begin with page views and the average page size, then account for caching. A high cache hit rate means the edge serves most bytes, and the origin sees mostly cache misses.

#Backups and replication

Treat this like a schedule. How much data is copied per run, and how often does it run in a month? Keep cross-region copies separate, since they often price differently, and they tend to stay steady even when user traffic fluctuates.

#Service-to-service traffic

Start with two numbers: how often one service calls another, and how much data each call exchanges. Multiply those values and scale the result to a month. Keep same-zone and cross-zone traffic separate because they can land in different pricing buckets.

Here is a small example. A checkout service calls an inventory service 10 times per second. Each response is about 15 KB. That is 150 KB per second. Over a 30-day month, that is roughly 370 GB of transfer.

#Turn byte totals into a monthly cost

Convert each route total into the unit the provider bills, such as GB or GiB. Price each bucket with the correct rule, such as internet egress, cross-zone, or cross-region. Apply free allowances and volume tiers last, after the monthly totals are clear.

#How to reduce data transfer costs

In the previous section, we listed the routes that generate charges and grouped them into simple buckets. That list is the starting point for cost reduction. Data transfer charges drop when fewer bytes cross paid boundaries.

The fastest gains usually come from the biggest route on the bill. Once that route is under control, the smaller ones become easier to evaluate.

#Reduce internet egress without breaking user experience

#Cache more at the edge

A CDN reduces origin egress by serving repeated requests from cache. It also improves load time for users. Cache rules, cache keys, and cache hit rate matter most here. A higher hit rate means fewer bytes leave the origin.

#Send fewer responses

Large responses become expensive because they are delivered repeatedly. Compression helps, but payload size often matters more. Trimming unused fields, paging large lists, and avoiding oversized defaults usually cuts transfer without changing functionality.

#Stop proxying downloads through the app

Egress often spikes when the application sits in the middle of file delivery. Large assets are usually better served directly from object storage or a CDN.

#Cut cross-zone traffic with better placement

Cross-zone transfer often appears when dependent services run across multiple zones without a clear placement strategy. High-frequency service calls are usually the main driver. When two components depend on each other on the hot path, placing them in the same zone reduces both latency and transfer volume.

Resilience still matters. A practical pattern is to keep the primary request path within one zone, then use replicas in other zones for failover and read scaling. This limits cross-zone traffic to replication and controlled synchronization, rather than constant back-and-forth calls.

#Reduce cross-region transfer by selective replication

Cross-region replication is easy to justify and overuse. Not every dataset needs to move across regions on a tight schedule. The clearest savings come from narrowing what is replicated and how often it moves.

Backups are a common source of steady transfer. Reduce frequency when it exceeds recovery needs and avoid copying the same full dataset repeatedly. Prioritize incremental backups and snapshot-based approaches when the platform supports them.

#Control cloud-to-cloud traffic by consolidating flows

Cloud-to-cloud transfer often grows quietly. Logs, metrics, sync jobs, and background exports are common sources.

Costs drop when there is one clear integration path instead of many. A shared internal gateway, pipeline, or export service often reduces duplication. Keeping large datasets in one primary location also helps, then exposing only what other systems need through smaller, targeted APIs.

#Remove extra meters in the path

In-path processing charges appear when traffic runs through a metered network service. NAT gateways are a common source, and load balancers can also add usage-based charges. On the bill, this usually shows up as lines tied to data processed, bytes processed, or usage units, not just hourly runtime.

Costs drop when traffic stops taking unnecessary detours. Internal traffic stays on internal paths, instead of leaving through NAT and returning. Private access paths to managed services can also reduce how much traffic flows through metered gateways.

Volume still matters. Package downloads, image pulls, and update checks can add up fast across many servers. Caching common dependencies and reusing base images often reduces this traffic without changing the architecture.

#Confirm the impact after each change

In the previous section, we grouped the estimate into a few clear buckets, such as internet egress, cross-zone, cross-region, and in-path processing. Those same buckets make validation straightforward.

After making a change, check the one bucket you intended to affect. Compare the monthly total to the prior baseline, or compare a shorter window if the change was recent. The goal is not to chase every small fluctuation. It is to confirm that the main route you targeted actually dropped, then move on to the next largest driver.

#Recent regulatory updates affecting egress fees

Egress fees and cloud switching charges are changing in the EU, and it is starting to influence how providers price multicloud transfer. The EU Data Act has been in effect since September 12, 2025, and it is designed to reduce barriers that make it hard or expensive to switch providers or run across multiple clouds.

In September 2025, Google introduced Data Transfer Essentials for EU and UK customers. This targets multicloud workloads that run in parallel across two or more providers under the same organization. Qualifying is metered separately and appears on the bill at zero charge, while other traffic continues to follow the usual network tier pricing rules.

This is not the end of transfer charges, but it is an important shift to track. The same EU framework also points toward a stricter end date in 2027, when switching charges, including egress charges tied to switching, are expected to be removed.

#Conclusion

Data transfer pricing becomes easier to manage once the routes are clear. The highest costs usually come from a few repeat paths, such as internet egress, cross-zone traffic, cross-region copies, and metered services in the middle. When we map those routes and total the bytes, bills become more predictable.

The most reliable cost reductions come from the same approach. Reduce the bytes leaving the system, keep high-volume traffic away from expensive boundaries, and remove extra meters in the path when possible. Then, validate the change against the same buckets used in the estimate. That is how transfer costs stay predictable as the workload grows.

Read how staking provider Chainode Tech improved their performance and uptime by choosing Cherry Servers' dedicated bare metal cloud over hyperscalers and VPS.

FAQs

What are data egress fees?

Data egress fees are charges for sending data out of a provider’s network, often listed as data transfer out or outbound data transfer. They usually apply when traffic goes to the public internet or to another provider.

Is inbound data transfer usually free?

Inbound data transfer is often not billed, but costs still appear when requests trigger outbound responses or when traffic crosses chargeable boundaries, such as zones or regions. The route still matters, even when the inbound transfer is not billed.

Does a CDN reduce data transfer costs?

A CDN can reduce origin egress by serving repeat requests from cache at the edge, which means fewer bytes leave the origin. The cost can shift to CDN delivery charges, so the total depends on cache hit rate, content type, and traffic volume.

What is the difference between bandwidth and data transfer?

Bandwidth is the speed of a network link. It tells how fast data can move, such as Mbps or Gbps. Data transfer is the total amount of data moved over time, usually measured in GB or GiB per month. Providers price data transfer by volume, not by speed.

Cherry Servers’ bare metal cloud—flexible and cost-effective alternative to hyperscale cloud.